I suppose you could call it a smock—a shapeless jacket of cheap grey fabric. We wore them to shield our clothes from printers ink. We were the clippers in Newsweek’s reference library/morgue who spent much of our workday reading newspapers, searching out and clipping articles to feed the needs of staff writers. In 1967 there was no “on line.” What news there was was in print or on the evening network news. The country relied on newspaper reporters to reveal what was happening, and every major city had competing presses.

I was a master of trivia in those days, a current affairs expert, and probably a drag to be around. The Newsweek building was on Madison Avenue. I wore my one suit and a tie every day for minimum Newspaper Guild wages. Beside my desk was an industrial-size trash barrel that would be full of perused newspapers by the end of the day. It seemed like everyone smoked. Amazing there were no fires. There were no women.

I was going full-time to night school at City College, up on the edge of Harlem. There was this thing called the draft back then. As long as I stayed matriculated fulltime I was eligible for a student deferment, which would keep me out of Southeast Asia jungles, or Canada, or jail. Wearing a suit and tie was a small price to pay for the freedom from being treated like disposable dirt. Night school at CCNY in the late ’60s is another story. The civil rights strikes, campus lock-ins, and police stand-offs. Harlem streets on the night Martin Luther King Jr. was shot.

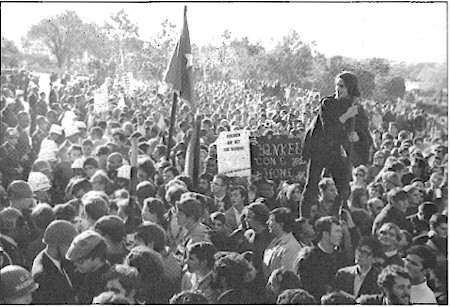

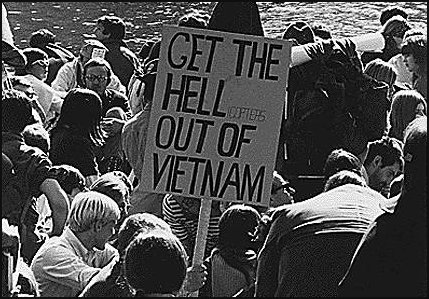

If you were alive then and there, you were on a side. I was with the protesters—a peacenik,, sit-in sitter, protest sign painter—in an unfortunately humor-deprived world split along a largely generational divide. The old folks had dismissed us, and we welcomed that. I advised draft dodgers. For a while my father banned me from his house. My oldest brother, a National Guard vet, picked a fight. When plans emerged for a united national anti-war demonstration in Washington, I got involved in organizing a New York City contingent.

We called our collected goals and actions the Movement, and this was before tectonic plates were discovered. If you were part of the Movement, you were wary of leaders. It was popular to claim that we all were in charge and that decisions were made by consensus. So, there were was no leader in the busload of amateur rebels we put together from the Lower East Side. The Peace Parade Committee paid for the rundown bus, and I got an address in ghetto D.C. where some of us could crash while there.

At Newsweek I went to my boss and told him I would be taking that Monday off. When he asked why, I told him I would be coming back from the weekend rally in D.C. When his reaction was neither approval nor disapproval, I proposed filing an observer’s report, background for whatever story the nation desk might choose to run on the event. He was a preternaturally skeptical man. I was not a reporter. I was a clipper. He said he would get back to me. It didn’t matter one way or the other. I was surprised when he came through. File my report, he told me. He would count it as Monday’s work. He couldn’t get me a press pass, but he gave me an official-looking nametag that identified me as a Newsweek employee.

There is no copy of what I filed. I spent Monday night typing up good copy and handed it in Tuesday ahead of deadline. Xerox was not a ready option sixty years ago. There are other versions of that chaotic, sometimes sickly brutal weekend. Mailer won awards for his. I watched federal marshals in cheap baggy suits enjoying their pummeling bloody young women sitting cross legged in front of me before dragging them off. Behind us was a line of soldiers with fixed bayonets. I really had to take a piss and, showing my Newsweek ID, I persuaded a nervous young officer to let me escape through their lines. It was not a moment to be proud of.

When advance copies of a week’s issue arrived at Newsweek all other work would stop to behold the object of our labors. What hath been made of them? The Pentagon did not make the cover. Instead there was a long-planned hit piece—“Trouble in Hippieland”—about what was being called the “counterculture.” A pearl-clutcher’s truffle on the evil-filled underworld of drugs, free love, and squalid poverty to which suburban kids were fleeing, it focused on two gruesome murders in the East Village.

The march on the Pentagon headed up national coverage—a sympatico segue. An anti-war protest was a warning that the counterculture malaise was dangerously festering. In Newsweek’s coverage, the march and protest were nothingmore than a riot and the participants traitors. The official crowd estimates of 100,000 in the march and 50,000 at the Pentagon sit-in were not mentioned, but the number of arrests, 648, was given and a wild guess was made at the tons of garbage left behind. All government press release stuff, not a word of the Movement’s goals or the march’s purpose. The photos were all UPI or AP. I wondered if Newsweek had any reporters there at all. There was nothing from my report.

In my twenties I wasn’t much into premeditation. I know what I did next that day required no advance consideration. I stood up, tore my copy of the magazine in half, and tossed it into my refuse barrel. Then I took off that fucking grey smock and threw that in there, too. My co-clippers watched in silence as I left. I had no phone in my one-room place on East 3rd Street, so I never heard back from Newsweek.

Nicely done, JE.

What truly differentiates those days from these days, is that, in those days, while we could be arguing with others with completely different beliefs and objectives from our own, at least we were all arguing from a commonly accepted set of facts. We could like or hate those facts, but we all started from an accepted common reality.

No more. These days if I’m arguing with a Trumpist and I point to a tabletop firmly aligned parallel with the floor and say, “this is horizontal,” the answer I’ll most likely get is “no, that’s vertical.” No resolution is even possible without a shared reality as a basis…

LikeLiked by 1 person