Ah, the simple pleasures of a summer night—

a warm breeze of cricket sound through the house

a cold pale ale and news of

both the Yankees and the Mets

victorious against their closest rivals

—pain pills kicking in.

New Jerusalem News is the lead-off book in my new novel series The Dominick Chronicles, set in contemporary times in various parts of the U.S. New Jerusalem News is set in New England.

New Jerusalem News is the lead-off book in my new novel series The Dominick Chronicles, set in contemporary times in various parts of the U.S. New Jerusalem News is set in New England.

Dominick is always just passing through. He is a professional house guest of the well-to-do, who follows the sun from resort to resort. If he was once searching for something, he long ago disavowed it. His freedom depends on his detachment, and he tries to maintain that. In each of his inadvertent adventures Dominick’s status as the outsider leads to his being a suspect for crimes he did not commit. These are the obverse of police procedurals. They are perp procedurals, in which the unjustly accused must establish his innocence in order to escape and move on.

Dominick is an observer, an historian, a reluctant participant; but his nomad’s life as a perpetual guest insures that what’s next will always be different.

New Jerusalem News is available in hardcover, Kindle, and audiobook formats. It can be ordered through my website (www.johnenright.us), directly from Amazon.com, or through your local bookstore. Thanks to the generosity of Audible, I have some free copies of the audiobook to give away to the first three Reality Salad blogheads to respond in the comments and ask for one.

Summer reading (or listening, I guess) at its best! Be the first on your block! Order now and you won’t have to order later!

For all you serious language mechanics out there, here, from Mark Forsyth’s The Elements of Eloquence, is a reminder that, in English, adjectives go in this order:

Opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose-noun. So you can have a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife. But if you mess with that word order in the slightest you’ll sound like a maniac.

And also, as a reminder that every author needs an editor, here is one page of T.S. Eliot’s original draft of “The Waste Land” as edited by Ezra Pound (1915):

He called himself Cricket. It was somewhere in Wyoming. Not anywhere in Wyoming, but some town big enough to have at least one saloon, because that is where we met. Cricket was Mickey Rooney size and was carrying his life around in a knapsack on his back, just like I was. Our packs were leaning against the same wall by the door. He had a beat-up old guitar case as well.

He called himself Cricket. It was somewhere in Wyoming. Not anywhere in Wyoming, but some town big enough to have at least one saloon, because that is where we met. Cricket was Mickey Rooney size and was carrying his life around in a knapsack on his back, just like I was. Our packs were leaning against the same wall by the door. He had a beat-up old guitar case as well.

Some little men never lose their childlike eagerness to please. A way of getting by, I guess. Cricket made me think of a ukulele. In Hawaiian, uku lele means jumping louse—something small and white that hops around. It was the natives’ nickname for the Cockney Royal Navy tar who introduced them to the instrument. You can imagine someone who would garner a nickname like that. I forget his real name.

I was hitchhiking west. I had jumped my last ride at this town. It was getting on dusk, and I had had my fill of the backs of ranch pickup trucks for that day. I must have had enough cash for a couple of beers and a burger. Cricket was on the road, too, hitchhiking in the opposite direction. We hit the saloon at about the same time and ended up on adjacent stools at the strangers’ end of the bar.

This would have been in the late ‘70s. The golden age for hitchhikers in America was vanishing, but in the west at least we were still accepted. As a mode of transportation it had its negatives, but it was free and I was mostly broke, and going cross-country I could make as good time as on Greyhound. You also got to meet people, and you got to visit places you never would have otherwise, like that Wyoming saloon.

Cricket was an entertainer. In an earlier era he would have been called a minstrel. We were sitting there on our bar stools, sipping our cold draft Coors, exchanging those little trial pleasantries like strangers do, feeling each other out, when he pulled a harmonica out of a pocket and started humming soft little rifts through it as we talked, sort of absent mindedly, really, as if it was the most natural thing to do—carry on a conversation while noodling around on a mouth organ. He was just a happy-go-lucky little guy, kicking back with a beer and his Hohner.

Cricket was also sort of warming up. He played a little blues rift that caught the attention of others at the bar. Then he stopped and drank some beer. Someone down the bar asked if he knew a certain song. Cricket smiled and nodded and played a short version. Someone else had another request, and he played that. Now everyone at the bar was paying some level of attention. The bartender put two free fresh beers in front of us. Cricket went to his guitar case and took out a guitar that had seen many years of service. He went to an empty table near the door and our packs and motioned for me to bring our new beers over. He opened the guitar case in front of the table and started to strum on his guitar.

It wasn’t like he was entertaining. It was more like he was playing just for himself, or maybe for just the two of us strangers sitting at the front table. It wasn’t loud. He didn’t sing. He would pick out the beginning of a tune, then stop to tune his guitar, sip some beer and chat. “Know this one?” he’d ask me and then play the first few bars of some old country standard or Buddy Holly song. The general conversation in the saloon resumed, but at a lower level. I am not musical. I know enough to be just an audience.

We talked about where we were coming from and where we were going. The only pointed question he asked me was whether or not I was a Vietnam vet. “You look sort of damaged,” he said. “Just wondering why.” Then he launched into a fuller version of a tune I didn’t know. He bent down over his guitar to watch his fingers, still playing softly, getting lyrical in his licks.

When he finished, the saloon was almost quiet, except back by the pool table. “Awright,” someone at the bar said. “Give us Ramblin’ Man.” And, after taking another long drink of Coors, Cricket launched into an intricate and accurate, if more ruminative version of the Allman Brothers’ classic. The applause that followed was not loud or long, but it was real. Two more gratis draft beers arrived.

“Enough suds,” Cricket told the bartender who brought them over. “Make the rest Old Grand Dad on the rocks.”

Over the next few hours the drinks did keep coming, and Cricket kept playing as he drank. Sometimes he put the guitar aside and played the harmonica. The saloon got livelier as the evening progressed. I was getting drunk, and I had only paid for that first beer. At some point, a waitress brought us two bowls of chili with crackers, and we ate. As people left, they tossed folding money into Cricket’s open guitar case.

We were both staggering a bit as we left the saloon with our packs on our backs, Cricket carrying his guitar case. Even in his cowboy boots he was a foot shorter than I was. It was well after midnight. The last saloon patrons’ cars and pickups were driving away into the night. We hiked out of town on the highway. We knew we wouldn’t be going too far—far enough out of town and far enough off the highway to find a clear place in the sage brush to throw down our sleeping bags. Beyond the lights of the town the stars came down close. It would be a clear and dry night.

“It ain’t natural, sleeping alone in the wilderness,” Cricket said, as we cut off the empty highway into the brush. There was half a moon rising, enough to walk by, I didn’t say anything. I thought the opposite was true, that the reason for being out here was to be alone. We came to a spot where previous sojourners had stopped, a circular clearing that smelled of old campfires and urine. ”Home sweet,” Cricket said, dropping his guitar case and slipping his arms out of his knapsack straps.

“I’m going on,” I said. “This space isn’t for me.”

“Suit yourself,” Cricket said, “but you’ll never stop being a lonesome loser.”

I hiked a long ways that night, trying to get lost in the high desert.

The historical fact of the Vietnam War seems unavoidable, especially if you were an American male of draft age in those years. It was like a Berlin Wall that held you in on one side, limiting your options and actions. The only approved gate through that wall led to induction, boot camp, and jungle warfare in a bullshit cause. At an age of dubious choices, to serve or not to serve had a crisp Nietzschean either/or clarity. Yes, part of the decision had to do with authority—whether your life belonged to you or to some other, outer, abstract, if very enforceable, power. But an even stronger factor, I think, was the conviction that the whole American escapade in Southeast Asia was just fucked up from the start to whenever enough innocents would die to make it end. There is resisting authority and there is questioning authority. Not that the authorities can tell the difference.

The historical fact of the Vietnam War seems unavoidable, especially if you were an American male of draft age in those years. It was like a Berlin Wall that held you in on one side, limiting your options and actions. The only approved gate through that wall led to induction, boot camp, and jungle warfare in a bullshit cause. At an age of dubious choices, to serve or not to serve had a crisp Nietzschean either/or clarity. Yes, part of the decision had to do with authority—whether your life belonged to you or to some other, outer, abstract, if very enforceable, power. But an even stronger factor, I think, was the conviction that the whole American escapade in Southeast Asia was just fucked up from the start to whenever enough innocents would die to make it end. There is resisting authority and there is questioning authority. Not that the authorities can tell the difference.

While an undergrad in night school at CCNY I worked for the Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee, organizing the first mass anti-war protests in New York City. I volunteered my after-midnight hours to turning out flyers on the Socialist Workers Party’s mimeograph machines (remember that smell?). I was a Manhattan group leader for the first March on the Pentagon, where Allen Ginsberg and others tried to levitate the building, and instead hundreds were beaten senseless by redneck federal marshals with four-foot batons, as a line of soldiers with fixed bayonets behind the seated protestors pushed them forward into the gleeful G-man gang of blood-splattering pigs in cheap Sears suits and fedoras like my dad used to wear. I was there. I saw it. I escaped by flashing my Newsweek credentials at a freaked-out National Guard lieutenant no older than I was who let me through the line of bayonets. I wasn’t there to be a martyr. Back in New York, I filed my eyewitness account, which the editors totally ignored, reporting instead on the amount of trash the protestors had left behind. I quit Newsweek.

I was a draft-avoidance counselor and an efficient draft dodger myself. But I really didn’t like the mechanics of the movement—the meetings, the manifestos, the egos, the whackos, and the FBI spies. The Socialist Workers Party gang were especially gruesome and humorless, no, make that witless, the dogs of dogma. I think they were mostly undercover agents who didn’t enjoy their jobs very much. It is interesting that in those years I made no friends inside the movement, not a single lover.

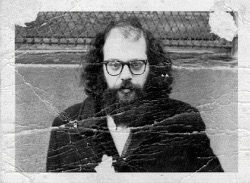

Well, I did turn one offer down. We were doing a sit-in/sleep-in occupation of an auditorium on campus, a sanctuary action for two AWOL draftees who didn’t want to go back to Nam. I was working logistics, getting food and water into the now police-cordoned-off protestors. Everyone was trying to keep the scene peaceful. Everyone knew that sooner or later (probably sooner) the protestors would return to their regular lives and the two AWOL dudes would be duly arrested and punished. For the third or fourth night, tired of protest rhetoric and sectarian rants, we arranged a read-in and invited as many sympathetic authors as we could muster. Our star attraction—the media took notice—was Allen Ginsberg.

After the reading, after the cameras had left, those of us remaining, a couple of hundred committed kids on a camp out, spread our blankets and sleeping bags on the auditorium floor. Allen came over and asked me very nicely, sweetly really, if he could share my sleeping bag. I had to say no. He held my hand for a minute, then kissed me on the cheek and ran his fingers through my hair the way a girl would. Then he smiled and left. There were plenty of sleeping bags there he could share that night.

The night that Lyndon Johnson went on TV to say he would not run for re-election, I got cosmically drunk on rum at Michael Joyce’s place then walked—stumbled—the streets of the Upper West Side, becoming soberingly aware of how little any of this really had to do with me.

A couple of years later, in Berkeley, a fellow anti-war activist had her purse snatched on campus. When she reported it to the campus police, they showed her photographs of possible suspects collected in several large photo albums. Later she told us, “You were all in there, all of you guys, all of my friends. Photos taken with telescopic lenses on campus. From the top of Sproul Hall at demonstrations, in the Plaza handing out flyers, talking to people at rallies. John, they even also had black and white photos of you from back in your New York days, very complimentary.”

Back in February I posted a blog about guns after that guy in Chapel Hill assassinated his three young Muslim neighbors over parking spaces. The only responses I got faulted me for not promoting universal open-carry laws to prevent such atrocities. Since then such NRA self-defense madness has only metastasized. There probably is no stopping it. I guess it is like whacking off—worse than pointless but it makes you feel good about yourself.

Back in February I posted a blog about guns after that guy in Chapel Hill assassinated his three young Muslim neighbors over parking spaces. The only responses I got faulted me for not promoting universal open-carry laws to prevent such atrocities. Since then such NRA self-defense madness has only metastasized. There probably is no stopping it. I guess it is like whacking off—worse than pointless but it makes you feel good about yourself.

From the New York Times (6/25/15):

But armed people are more likely to use guns to harm others or themselves rather than to kill in self-defense, according to a new Violence Policy Center study of federal records. In 2012, there were 259 justifiable homicides by a citizen with a gun, compared with 8,342 criminal homicides by armed citizens (plus tens of thousands of gun deaths in suicides and unintentional shootings).

Such numbers mean nothing to self-styled Rambos, for whom there is only one #1—themselves, carrying heat. Duh.

1966, Manhattan. Michael Joyce and I were sharing a railroad flat in Spanish Harlem. Michael was going daytime to that Catholic college in Brooklyn and working full time as night manager of the City Squire Hotel midtown. I was going full time to night school at CCNY and working days as a mail boy at Time-Life, Inc., in Rockefeller Center, pay around a hundred bucks a week, which was plenty. Each floor in the Time-Life Building had a mail room and a mail boy. We wore gray uniform jackets (never laundered) that identified us as that floor’s servant.

Somehow I got the executive floor, where the ceilings were higher than on any other floor and the secretaries all wore miniskirts with no stockings. It was a quiet floor, busy but quiet, reserved sort of. The best looking secretaries worked there, young with long legs. Executive assistants they called themselves. They enjoyed having someone below them to order around. I didn’t mind. My private domain—the mail room—was bigger than any of their cubicles.

I had all the big wigs, including Hedley Donovan, the editor and chief of everything, along with the head of foreign correspondents, so that all their confidential wires came through me. I also had Mr. Luce himself, the Old Man. Not yet dead, he still came into his imperial, walnut-paneled office once a week or so, on his way to or from some formal function. His secretary—the only older woman on the floor—was always there, keeper and guard of the founder’s sanctum sanctorum.

Mr. Luce got a fair amount of corporate mail, all of which came to me. Much of it, most of it, had nothing to do with Mr. Luce himself, but was about one of his publications—Time or Life or Fortune or Sports Illustrated. Part of my job was to open all of his mail, read it, and redirect it. I thought of myself as his shield, deflecting the arrows of his enemies. And his enemies were legion and often ungrammatical. Some of the nastiest letters were about his wife Claire Booth Luce. Those I just tossed in the trash. Serious threats I forwarded to the legal department. The man was well hated.

Out of every hundred letters maybe five made it through to his secretary—kiss-ass notes or thoughtful observations, an invitation or two, if I thought the sender was worthy. I never met Mr. Luce, never saw him come or go. I think he had his own elevator. He died that winter.

Hedley Donovan demanded twenty fresh, sharpened pencils in the two cups on his desk every morning—ten black No. 2s and ten reds—all the same height. He would use them all in the course of a day, and I would retrieve, resharpen, and recycle them all to the lesser editors. But on some late afternoons when everything had quieted down, I would sit at my mail room work station and feed Mr. Donovan’s used pencils one by one down to the unused erasers into the electric sharpener. Just for the hell of it, thinking of miniskirts.

It’s that time of year. Caps and gowns time. Canisius is the Jesuit high school in Buffalo that I graduated from 52 years ago.

It’s that time of year. Caps and gowns time. Canisius is the Jesuit high school in Buffalo that I graduated from 52 years ago.

Canisius High School Class of ’63

They say that armies are always trained

to re-fight the war that they last won.

Four years of Latin and a whole homeroom

lost to Greek; Father Riesert’s giant

slide rule above the blackboard of his

physics classroom; the unheated pool

where we naked water polo warred.

All the past was invested in us—

Caesar’s Gallic Wars and Shakespeare,

authority’s unquestioned dominance,

the sport coats and ties, dictated haircuts,

pride of place, and fear of jug.

All that was before.

Before Nam and napalm,

before Jimi Hendrix and the pill,

before foot prints on the moon,

before Joan Baez or hash brownies,

before satellites linking and stealing

our lives, or all the glaciers melting.

We who were born with the bomb

can bear witness to the before and after.

We have watched it all change—

black holes replacing purgatory,

irony supplanting orthodoxy.

Even the number of dimensions

has expanded beyond comprehension.

Amo, amas, amat — the first Latin

we were taught in freshman year.

Those Jesuits, they just sent us out

as raw recruits onto a battlefield

that Ignatius could never begin to imagine.

Would he have a website or a blog?

It has all been an end-game of sorts.

Whatever comes next will be more desperate.

But we did the best we could.

The end of the past follows us & just as well.

The future will be its own orphan.

The folks at the Special Collections and Archives of the University of Rhode Island Library have agreed to take my journals and papers for safe-keeping. So, for the past few days I have been busy getting all that in order to say goodbye to. The library gave me boxes in which to stash it all—fifty years’ worth, maybe 10,000 pages in all. The oldest of these files have followed me from Harlem to Berkeley to New Jersey to San Francisco to Samoa to Rhode Island. The 26 years of Samoa papers still retain the fond moldy smell of the islands.

The folks at the Special Collections and Archives of the University of Rhode Island Library have agreed to take my journals and papers for safe-keeping. So, for the past few days I have been busy getting all that in order to say goodbye to. The library gave me boxes in which to stash it all—fifty years’ worth, maybe 10,000 pages in all. The oldest of these files have followed me from Harlem to Berkeley to New Jersey to San Francisco to Samoa to Rhode Island. The 26 years of Samoa papers still retain the fond moldy smell of the islands.

There are at least a thousand poems and hundreds of pieces of both finished and abandoned prose to sort through. Every time I moved I threw away more than I kept, but there is still too much. I sort it all through yet another, final filter, filling black garbage bags with the less than necessary. So much paper waste—I have not lived a forest friendly life. But I do get to revisit raising my son in the benign bush of Tutuila and re-fear cyclones I had forgotten.

I’ll share a few pieces here, all from decades ago.

Desire

I want a t-shirt

that says on its back

Use Other Side First.

I want a ticket

that no one will question,

a friend in high places.

I want a history

where no one is named

and facts have no dates

but eons have names

like Nancy and Jane

where nothing happens.

Please pass the eraser.

Between us we can

get somewhere fast.

I just feel it rising

out of the sidewalk

and into my soul

nothing that I ever

needed or wanted

as naked as I am

as useless as cops

as salty as sex

as open as a wound.

I want an old day

to stop by and visit

to sit by the window

and tell me about

what the king will say

to the queen when they

finally are left alone

and all her sorrows

have dissolved in tears.

Santa Pajama

Santa Pajama was a bedroom community just up the coast from Vaudville. We drove up the coast road. The ocean was so calm it looked asleep. Samantha slathered sunblock onto her arms and face and shoulders. It was May.

When we got there I couldn’t find the place. I kept rereading the directions she’d taken down over the phone and kept getting lost. Samantha pretended to sleep.

What I finally found was the wrong place on the boardwalk above the beach. But the people there knew who Buddy was and sent us to a bar on the Vista Verde where we could find him. He wasn’t there but Samantha knew the bartender — remembered him from a Shinto halfway house up in Nofloss — so we stayed and drank diet maitais.

I found Buddy’s phone number on the on the toilet partition in the men’s room. I left a message for him on the machine that answered at a Swedish phonesex service. When I went back to the bar Samantha was gone and there was a new bartender. Her purse was still on the floor beside her empty barstool.

I slept in the car, in the back seat. I’m short. In the morning a 13 year old girl wearing a pair of men’s peach jockey shorts as a halter top and a pair of Italian roller skates was asleep in the front seat. I married her. We’ve got three kids now. We don’t live there anymore.

abc

anyway

because

creation

demands

eternal

fasting

gorging

healing

in order

just to know

looping

meaningless

nevertheless

operationally

pertinent

questions re:

recording

some-

times

unrelated

verasimilitudes

without which

xyz

Someone observed about the Buffalo I grew up in that there seemed to be a church on every block and two saloons at every intersection. They were all filled with good Christians. The typical neighborhood tavern carried the proprietor’s family name—Strinka’s, say, or Topolski’s or O’Connor’s—and had two entrances, one to the bar in front and another family entrance in the rear to the dining room. As most of the city was Catholic, these family entrances got most of their traffic on Fridays around dinner time, because the tavern’s cheap fish fry was a housewife’s welcome alternative to stinking up the house with the smell of cooking fish. And it was payday.

It was a blue-collar world. A shot of schnapps and a draft cost you fifty cents. For many the corner barroom was like another room on their house—a room free of family and kids. There were no TVs above the bar, no sports channels, and if there was a juke box it wasn’t tolerated during prime drinking hours, dusk to midnight, and for half the year dusk came early to Buffalo. Patrons either quietly conversed or sat alone inside the blessed freedom of their chosen cone of silence, studying their drinks and cigarettes, communing only with themselves and maybe their reflection in the back-bar mirror behind its picket fence of whiskey bottles. Normally everyone there would be a regular, and after a while bits of personal history would become absorbed as common knowledge and the men and women behind the bar became not just the dispensers of self-medication but also the reference librarians of local lore and current events.

“I haven’t seen Murphy in here in a week.”

“It’s his back again. You remember his accident.”

“Did the union ever get them assholes to settle?”

“I guess they’re paying for another operation.”

“How’s his wife doing?”

“She’s off the drink, too, I think. Hasn’t been in. Want another?”

If Murphy didn’t make it, there would be a collection for the widow and the kids.

I entered this world when I was seventeen, and for the next twenty years—until I moved to Samoa—neighborhood bars, no matter where they were, would be my wayside chapels of peace and familiarity. If during that time the Catholic Church ditched Latin as its unifying language, corner saloons still spoke the same lingo of escape and observed a consistent liturgy of nonjudgmental sanctuary, filled with your fellow faithful. Homes away from home, the other room to your ancestral house that you could always find if you walked the streets and could interpret the neon semiotics of barroom windows.

I spent several years visiting, photographing, and researching the scattered remaining historic saloons of the California Gold Rush and Nevada Mother Lode country for a book I never wrote. I used to pride myself if plopped down in a new town—at a Greyhound Bus Station say—of being able to find on instinct the nearest convivial watering hole. I wonder how many thousands of such places I’ve walked into, just a stranger coming in the door and taking a stool at the bar and ordering a drink. Just do it right and nobody will ever question you. It is like entering a church and dipping your right hand into the holy water font and blessing yourself and genuflecting properly before the altar. In twenty years no one ever challenged me or tried to pick a quarrel. From Hong Kong to Belfast, in twenty different countries and every state of the union the sacrament was the same.

And so it was in North Beach where I found Specs’. I never lived in that part of San Francisco, but Specs’ became my neighborhood bar. I am a tad superstitious about talking about Specs’, because the place, which absorbed me forty years ago, is still there, just off Columbus Avenue on old Adler (now Saroyan) Alley, unchanged, ungentrified, and I am afeared to jinx its existence by writing about it as history. (Is this aging, when you begin to feel some responsibility for the past, some complicity with its integrity and survival?) I moved often in those years, both around and away from the Bay Area, but Specs’ Museum and Saloon remained a sort of borrowed nexus, the place where people could find me if I was in town or leave messages for me if I wasn’t. A place to find connections for work or the next apartment to rent or a new lover. But mainly it was a place to talk, a bohemian wayback machine. Again there was no TV set in the place nor a juke box. The bartenders were Irish maestros of gab. I made some good friends there, folks always ready to pick up the talk no matter where it had left off, folks who just wanted cohorts and a space to enjoy the end of their day.

A number of years ago I stopped in Specs’ on my way through San Francisco to somewhere else. It had been three or four years since my last in transit visit. I hung out at City Lights Books across the avenue until Specs’ opened after four. I took my old seat at the end of the bar between the front window and the reading lamp and opened a book I’d just bought. The bartender, a younger man whom I’d never seen before, was busy setting up the bar for business. I didn’t bother him with an order. All the memorabilia of the bar—the flags and shark jaws, old union posters and ironic signs, scrimshaw and Inuit art, framed newspaper headlines and eclectic photos—were all still in there proper places, all sepia stained like Civil War prints by decades of cigarette smoke. Then a green sixteen-ounce can of Rainer Ale appeared on a coaster in front of me. Green Death we used to call it, the strongest, most assertive brew you could buy there, the usual opening drink of the old sundown regulars thirty-five years before.

“What’s this?” I said to the unknown barkeep.

“You’re Enright, aren’t ya?” he answered, straight out of Dublin. “And that’s your usual, ain’t it? Where ya bin?”

I came back late that night, before closing. A different crowd, all younger, only a few of the old, hobbled and roseola-nosed regulars left. I came back to see the eponymous proprietor Richard “Specs” Simmons himself, who, dapper still in his 70s, would stop by to judge the closing crowd. We were glad to meet. We sat at a table near the front and talked the present about the past, as men will, catching up on people and their personal events—Deborah’s kids, Marilyn’s last known success, Kent’s funeral. Since my previous visit San Francisco had passed a law against tobacco smoking in all public places, including saloons, and now the dead-end pedestrian alleyway in front of Specs’ often held the best conversations, as smokers followed one another outside, placing coasters on top of their drinks on the bar. But when Specs lit a cigarette without moving from his table, I did too.

“It’s my place, after all,” he said. “If anyone wants to file a complaint, then fuck ‘em. They’re eighty-sixed forever and may they remain eternally childless.” He took a drag. “And I’ll gladly pay the fucking fine.”

Usual Group at the Window Table

____________________

How in Westerns the wheels of the wagons

always spin backwards the faster they go,

how ice and flame at first touch feel the same.

Take a pint and a seat by the window.

If all my sins were confessed in Islam

my body would have no extremities.

What do you call what you want to forget?

Take a pint and a seat by the window.

There are faults in the sky that insult me,

slick birds with no wings that call themselves souls.

Without your lost beauty no one knows you.

Take a pint and a seat by the window