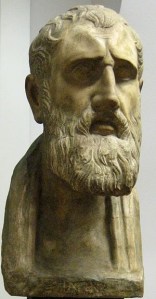

Specs himself outside his saloon, having a smoke and a laugh, 2004

Someone observed about the Buffalo I grew up in that there seemed to be a church on every block and two saloons at every intersection. They were all filled with good Christians. The typical neighborhood tavern carried the proprietor’s family name—Strinka’s, say, or Topolski’s or O’Connor’s—and had two entrances, one to the bar in front and another family entrance in the rear to the dining room. As most of the city was Catholic, these family entrances got most of their traffic on Fridays around dinner time, because the tavern’s cheap fish fry was a housewife’s welcome alternative to stinking up the house with the smell of cooking fish. And it was payday.

It was a blue-collar world. A shot of schnapps and a draft cost you fifty cents. For many the corner barroom was like another room on their house—a room free of family and kids. There were no TVs above the bar, no sports channels, and if there was a juke box it wasn’t tolerated during prime drinking hours, dusk to midnight, and for half the year dusk came early to Buffalo. Patrons either quietly conversed or sat alone inside the blessed freedom of their chosen cone of silence, studying their drinks and cigarettes, communing only with themselves and maybe their reflection in the back-bar mirror behind its picket fence of whiskey bottles. Normally everyone there would be a regular, and after a while bits of personal history would become absorbed as common knowledge and the men and women behind the bar became not just the dispensers of self-medication but also the reference librarians of local lore and current events.

“I haven’t seen Murphy in here in a week.”

“It’s his back again. You remember his accident.”

“Did the union ever get them assholes to settle?”

“I guess they’re paying for another operation.”

“How’s his wife doing?”

“She’s off the drink, too, I think. Hasn’t been in. Want another?”

If Murphy didn’t make it, there would be a collection for the widow and the kids.

I entered this world when I was seventeen, and for the next twenty years—until I moved to Samoa—neighborhood bars, no matter where they were, would be my wayside chapels of peace and familiarity. If during that time the Catholic Church ditched Latin as its unifying language, corner saloons still spoke the same lingo of escape and observed a consistent liturgy of nonjudgmental sanctuary, filled with your fellow faithful. Homes away from home, the other room to your ancestral house that you could always find if you walked the streets and could interpret the neon semiotics of barroom windows.

I spent several years visiting, photographing, and researching the scattered remaining historic saloons of the California Gold Rush and Nevada Mother Lode country for a book I never wrote. I used to pride myself if plopped down in a new town—at a Greyhound Bus Station say—of being able to find on instinct the nearest convivial watering hole. I wonder how many thousands of such places I’ve walked into, just a stranger coming in the door and taking a stool at the bar and ordering a drink. Just do it right and nobody will ever question you. It is like entering a church and dipping your right hand into the holy water font and blessing yourself and genuflecting properly before the altar. In twenty years no one ever challenged me or tried to pick a quarrel. From Hong Kong to Belfast, in twenty different countries and every state of the union the sacrament was the same.

And so it was in North Beach where I found Specs’. I never lived in that part of San Francisco, but Specs’ became my neighborhood bar. I am a tad superstitious about talking about Specs’, because the place, which absorbed me forty years ago, is still there, just off Columbus Avenue on old Adler (now Saroyan) Alley, unchanged, ungentrified, and I am afeared to jinx its existence by writing about it as history. (Is this aging, when you begin to feel some responsibility for the past, some complicity with its integrity and survival?) I moved often in those years, both around and away from the Bay Area, but Specs’ Museum and Saloon remained a sort of borrowed nexus, the place where people could find me if I was in town or leave messages for me if I wasn’t. A place to find connections for work or the next apartment to rent or a new lover. But mainly it was a place to talk, a bohemian wayback machine. Again there was no TV set in the place nor a juke box. The bartenders were Irish maestros of gab. I made some good friends there, folks always ready to pick up the talk no matter where it had left off, folks who just wanted cohorts and a space to enjoy the end of their day.

A number of years ago I stopped in Specs’ on my way through San Francisco to somewhere else. It had been three or four years since my last in transit visit. I hung out at City Lights Books across the avenue until Specs’ opened after four. I took my old seat at the end of the bar between the front window and the reading lamp and opened a book I’d just bought. The bartender, a younger man whom I’d never seen before, was busy setting up the bar for business. I didn’t bother him with an order. All the memorabilia of the bar—the flags and shark jaws, old union posters and ironic signs, scrimshaw and Inuit art, framed newspaper headlines and eclectic photos—were all still in there proper places, all sepia stained like Civil War prints by decades of cigarette smoke. Then a green sixteen-ounce can of Rainer Ale appeared on a coaster in front of me. Green Death we used to call it, the strongest, most assertive brew you could buy there, the usual opening drink of the old sundown regulars thirty-five years before.

“What’s this?” I said to the unknown barkeep.

“You’re Enright, aren’t ya?” he answered, straight out of Dublin. “And that’s your usual, ain’t it? Where ya bin?”

I came back late that night, before closing. A different crowd, all younger, only a few of the old, hobbled and roseola-nosed regulars left. I came back to see the eponymous proprietor Richard “Specs” Simmons himself, who, dapper still in his 70s, would stop by to judge the closing crowd. We were glad to meet. We sat at a table near the front and talked the present about the past, as men will, catching up on people and their personal events—Deborah’s kids, Marilyn’s last known success, Kent’s funeral. Since my previous visit San Francisco had passed a law against tobacco smoking in all public places, including saloons, and now the dead-end pedestrian alleyway in front of Specs’ often held the best conversations, as smokers followed one another outside, placing coasters on top of their drinks on the bar. But when Specs lit a cigarette without moving from his table, I did too.

“It’s my place, after all,” he said. “If anyone wants to file a complaint, then fuck ‘em. They’re eighty-sixed forever and may they remain eternally childless.” He took a drag. “And I’ll gladly pay the fucking fine.”

Usual Group at the Window Table

____________________

How in Westerns the wheels of the wagons

always spin backwards the faster they go,

how ice and flame at first touch feel the same.

Take a pint and a seat by the window.

If all my sins were confessed in Islam

my body would have no extremities.

What do you call what you want to forget?

Take a pint and a seat by the window.

There are faults in the sky that insult me,

slick birds with no wings that call themselves souls.

Without your lost beauty no one knows you.

Take a pint and a seat by the window

It’s that time of year. Caps and gowns time. Canisius is the Jesuit high school in Buffalo that I graduated from 52 years ago.

It’s that time of year. Caps and gowns time. Canisius is the Jesuit high school in Buffalo that I graduated from 52 years ago.